When Your Wish Can Go Too Far

How problematic acquisitions and lack of a clear strategy have left the Mouse feeling trapped

By Abigail Iaconis, Capstone Senior Analyst

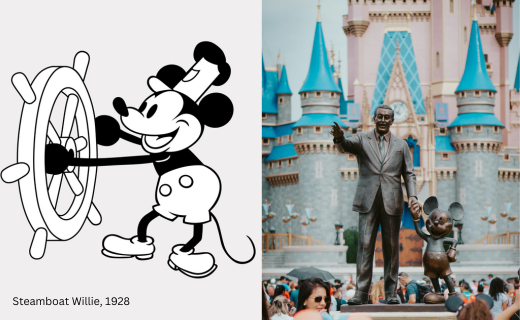

The Walt Disney Corporation has one of the most iconic brand images on Earth. Founded as the humbly named Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio in 1923, the company has shaped mass market entertainment and popular culture for a century. Disney’s creations and captivating content revolutionized motion pictures, television, and theme parks. There was no reason to think that Disney’s influence would wane as it rolled into the digital age acquiring additional film franchises, scooping up TV networks, and launching its powerful streaming service.

Yet, in the midst of its centennial celebration, Disney found itself dealing with substantial financial losses. For those of us in the business consulting world, it provides a real-life case study of how even corporate behemoths can suffer consequences when they stray too far from their strategic growth goals.

In just four years, Disney went from ruling the box office to playing catch-up with other studios after a series of cinematic flops. Part of this downward trajectory was due to the deterioration of the Marvel brand of superhero movies after hitting a peak in 2019. When Disney acquired Marvel in December 2009, what we now know as the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) had just begun a year and a half earlier with the release of Iron Man. Iron Man would act as the catalyst for more than twenty box office hits and an elaborate, intertwined storyline that would unfold over the next 11 years and culminate in the smash release of Avengers: Endgame in 2019. Since Endgame, the MCU has added 11 movies and 12 television series released directly to Disney+ (plus 1 Christmas special to boot), but the allure and cohesion of the Avengers brand have all but completely faded away.

Beyond Marvel, Disney’s box office woes can also be attributed to audiences everywhere growing increasingly tired of “live action” remakes of Disney favorites like Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, and The Little Mermaid. The same could be said about the variety of sequels and prequels that have come out in recent years (Christopher Robin (2018), Lightyear (2022), Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023), etc.). While, legally, these remakes have not extended any of Disney’s original copyrights, these semi-reimagined versions of beloved tales have successfully created a swath of new copyright protections that will outlive the copyrights of the original animated versions. And although “renewing” numerous copyrights is a very strategic endeavor, audiences are seeing right through it. After a decade or so of announcing remake after remake, this behavior has knocked Disney off the proverbial pedestal, even for many life-long Disney fanatics.

At the end of the day, the root of the problem at this pivotal point in the entertainment industry is that Disney’s “core” audience has become far too large as a result of decades of diversification.

Despite a very popular initial rollout in 2019, with a whopping 73.7 million subscribers in its first year, the Disney+ streaming service saw a significant drop in revenue in 2023. Disney is not alone in this downward trajectory. Due to rising costs across most streaming services, consumers are having to choose which services they’d like to keep and which could fall by the wayside. Unlike other big names in streaming, Disney+ is focused exclusively on their own brand, while competitors like Netflix and Max have both content from their own brands as well as other sources. In general, as streaming services continue to raise subscription costs, offer lower-priced subscriptions with advertising, and create more ways to bundle, the streaming space will begin to resemble a modern version of traditional cable TV.

In the world of M&A, we often come across the phrase “serial acquirer”. Simply put, it means a company has made buying other businesses a central element of their growth strategy. This certainly applies to Disney in terms of acquiring television networks, rival studios, and the like. The misstep that can often occur with serial acquisition, even for well-established companies, is that they become so focused on completing an acquisition that they fail to fully consider if the company they are acquiring is a good fit.

So, should Disney jettison some of the assets it was so quick to acquire? That’s a difficult call to make, which is probably why Disney has been waffling on this decision for months. In July 2023, during the actors and writers strikes, CEO Bob Iger shared that he was open to spinning off the cable entertainment networks – taking Disney out of the linear TV business as viewers rapidly shift to direct-to-consumer streaming services. However, by November 2023, Iger completely changed his stance and said Disney would keep the TV networks.

One of the most important aspects of business at Disney’s scale is diversification. But no amount of traditional diversification and acquisition could have prepared Disney for the disruptive trends of today’s digital transformation, much less the upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. To keep up with their debts and alleviate some of the strain of straddling the direct-to-consumer business and traditional TV, it’s no wonder Disney has been considering selling ABC and other assets.

The pressure on inorganic growth initiatives to financially compensate for organic growth failures forces Disney’s assets out of balance. Disney’s internal growth strategies – product development and market penetration – have not paid off enough in recent years. Apart from the continued investment in their theme parks, which serve as a major source of income, Disney’s organic revenue streams – such as recent film releases, like Haunted Mansion and The Marvels, and Disney+ – have failed to generate as much growth as originally expected.

At the end of the day, the root of the problem at this pivotal point in the entertainment industry is that Disney’s “core” audience has become far too large as a result of decades of diversification. To better align their assets and growth initiatives for today’s digital age, Disney needs to figure out who exactly their customers are. It appears some of these acquisitions are distracting Disney from the lifeblood of what projected the company to superstardom in the first place.

At the grand opening of Disneyland in 1955, Walt Disney remarked, “Here age relives fond memories of the past, and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future”. Disney must strike a delicate balance between evolving for today’s world and staying true to who they’ve been since two brothers opened a cartoon studio in California.

Like many great stories – including those told by Disney itself – sometimes the answers to your biggest problems have been with you from the start. Tapping into the creative potential of their team and retraining The Mouse for the next generation will help realign Disney’s compass as they continue on to the “second star to the right and straight on ‘til morning”.